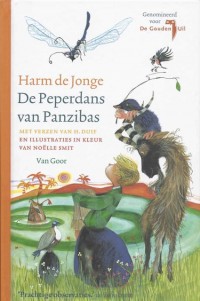

The Pepperdance of Panzibas 2004

he ventures on the genre of beast-fable for the first time. This book is nominated for the Belgian prize The Golden Owl. The Pepperdance of Panzibas is a beast-fable about life and death, about hope and desires, about love and fidelity, about fears and courage.

It is the story of Manne Man, who adores peppermint, Bobél, the exceedingly beautiful princess of Zanzibar, and the twelve animals, amongst whom:

Mr. Pigeon, the aristocratic poet who regales himself on words and writes down verses with a bird’s feather

Moody Mole, the gloomy grumbler who knows so many things about Death

Air Grasshopper, the young daredevil who goes to Panzibas on his sneakers ‘to live backwards’

Tellwhy Dragonfly, the brisk dancing-girl, who would love to learn how to kiss

Sarah Snail, the problem child who has not got any bones in her body and is afraid of melting away completely

Harry Oldgoat, the old trimmer of branches who gets swept of his feet when he smells Dragonfly’s scent of raspberries

Trembly Woodmouse, the shy little drudge who gets startled so easily and would like to be a boa constrictor

Daddy Toad, the conceited chairman who adores tender bluebottles and who knows all about the island of fortune, Panzibas.

Harm de Jonge’s books have been translated into German, French, Hebrew, Korean and Turkish.

Interested? Click here to read a chapter.

The Pepperdance of Panzibas 2004

Translation by Annelies Jorna

Pictures Noëlle Smit

The lilies were having a snooze on the pool’s surface. The buttercups were humming in the sunshine. A water beetle was swimming on its back and counting the stripes on its belly.

Manne Man was sitting on the Blue Stone with his feet in the water. He was sucking a peppermint. When sitting on the Blue Stone he saw what no one else saw. When sucking a peppermint he heard what no one else heard.

2 A robin’s feather for a love poem

Manne Man was prising a peppermint out of its packet.

‘Mr Pigeon,’ he said. ‘How should one go about writing a poem?’

Mr Pigeon smoothed the feathers on his head and looked thoughtful.

‘I would prefer to speak of verse,’ he said. ‘One writes verse with feathers. For merry verse you need a bluetit’s feather. It has the words dancing with blueishness. A crow’s pen is used for writing about death. And for winter verse you would, of course, pick a feather from the snowy owl. Any verse needs its very own writing feather.’

He looked about him with one eye open and by the beat of a wing he chased off Gertrude Gnat.

‘Shall I write you some love verse, Manne? I happen to have a beautifully pointed robin’s feather in my pocket. Or are you ready for a wedding invitation yet? I would have to find me a swan’s feather then.’

Pidgeon did not wait for an answer. He flew into a white poplar and returned with a leaf in his beak. He stroked it until it was beautifully smooth.

‘A poet always uses soft words,’ he said. ‘But for a love poem you want particularly soft ones. Words like: fluffydove and downymoss. Never ever choose words with precise s’es, such as sharp and shift and shout. Such words are glaringly yellow and impossibly stingy.’

Pigeon swallowed a peppercorn and licked the robin’s feather. He tilted his head and watched Manne pensively.

‘I take it her name is Annebine?’ he said. ‘And she is bound to have two braids. In love poems female persons usually have braids.’

Manne was thinking of Bobél who sat near him in school. Bobél was born in Zanzibar . She was as brown as chocolate. To the side of her head she had one tiny braid. It had even tinier red beads in it, bobbing across her cheek when she moved. Twelve tiny beads: Manne had counted them often enough.

‘Her name is Bobél,’ he said, ‘and she is a princess from Zanzibar . She is the sweetest girl in class. Write verse for Bobél, Pigeon.’

‘I’m afraid the name won’t do,’ Pigeon said. ‘Bobél rhymes with hell and shell. And Zanzibar with fancy tar. It might have worked if it had been something like Panzibas. But this way the verse would become nonsense. Annebine it must be! Now there’s a name which takes you to pepperwine and sweet love o’ mine on its own accord.’

Mr Pigeon stared up into the sky and considered. Then he wrote a love poem. He did so very lightly: the robin’s feather hardly touched the leaf. Occasionally, Pigeon looked at Manne and winked in a friendly manner. When he was finished, he beckoned Manne to come closer.

‘After such verse there is a shaky croak to my voice,’ he croaked. ‘Would you read it aloud, Manne? And do make the words dance like butterflies.’

Some of the animals were listening along. Daddy Toad went and lay on his back in the moss. Tellwhy Dragonfly found herself a spot on a waterlily. Air Grasshopper coolly swung on one leg from a reed stem. Manne took the peppermint out of his mouth and read:

My sweet Annebine.

Your tiny ears are fine.

In crispy, wispy, jolly line.

Are your cheeks as smooth as wine?

Oh, my tender Annebine.

Will you be for ever mine!